Grad school has me busy, far busier than I expected, which has dramatically cut down on the work I am able to do on my world. However, one of my classes focuses upon medieval liturgical life, with an emphasis on monasteries - it's where I found the source for my previous post. I have no idea how much work I'll be able to get done, but as I come across these kinds of gems, I'll post them - when I have more time, I'll collate them into a different idea of the 'cleric,' perhaps called the 'cantor' or something similar.

Today's insights come from Susan Boynton's article, "Orality, Literacy, and the Early Notation of the Office Hymns." It's a fascinating text on the relationship between oral and written traditions in the 11th c. While rather technical and detail-oriented, the scholarship is phenomenal.

The monks of Cluny, a Burgundian abbey, attracted widespread renown for their wholesomeness and purity, inspiring many other monasteries to follow their customs (at least, in theory). Consequently, the Clunaic monks produced dozens of texts called 'customaries' which listed the ways they practiced their faith, "including its liturgy, the duties of monastic officials, and the routine of daily life in the community" (135).

The reason for this admiration, and the purpose of this post, is that the purity of these monks was believed to grant divine power: "the abbey's fabled way of life... in addition to its salvific power through intercessory prayer for the dead, was thought by some to transform monks into angels. The training of oblates at Cluny... aimed to instill in them the purity that would enable them to lead a celestial life on [sic] earth..." (136).

The parallel between this and becoming a Buddha by reaching Enlightenment are striking.

I guess the takeaway is that the reward for a character who's powers come from a divine authority (at least within some sort of Christian-ish tradition) is becoming an angel and still dwelling on Earth. Do with that what you will.

Thursday, September 29, 2016

Saturday, September 17, 2016

Trade Equations

I have, potentially,

my first game on Monday. It's at a local

gaming store, but since it's during the weekday, it should be relatively

quiet. Because of this, I have been

frantically working at the trade tables to get them into a useable state - it

also keeps me distracted from the schoolwork that needs to be done this weekend

as well.

I was completing the

second step in the process, aggregating all of my world's references into

thematic groups with some rudimentary determination of goods that require no

processing, when I ran into two problems.

Before I get into

this, if you are not familiar with Alexis' trade tables, I suggest you fix that

- the following discussion will make no sense if you don't.

The first problem

was with the valuation of gold. This is

the first calculation on the sheet, and it's important because it determines

the price, in copper pieces, of 1 reference's worth of goods. For the sake of simplicity, I am calling that

quantity a crop. Right now, a resource's crop size is

determined by dividing the global production of that resource by all of the

references for it (on a global scale).

It struck me as a

little odd that the gold crop had no direct bearing on the local value of

gold. Then I started digging a little

further and it appeared that the price of gold would only fluctuate based upon

.002*local/global, where local is the number of local references of gold and

global is the total number of gold references.

This seemed strange to me, but I continued forward.

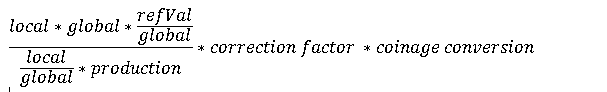

What convinced me

that this was a problem, though, was the double-conversion to coinage seen

whenever the price of a good was to be generated. The formula for an arbitrary good looked

something like this,

Where refVal is the

value in copper pieces of 1 reference, calculated as above and production is

the global quantity of a good produced.

This simplifies to

Which means that the

local amount of a reference has no significant bearing upon its price. Additionally, since refVal has already

converted from oz. gold to copper coins, the additional coin conversion at the

end of the equation is extraneous.

Which means that I

needed a new way to value gold and a new way to assign a coin value to 1 unit

of a resource. I called in my roommate

and we spent half the night yesterday/this morning fighting through this to find

a solution. And find one we did.

The challenge of

this problem is that there are so few actual variables that depend upon

location - every meaningful combination of them resulted in their cancellation,

which defeated the purpose of the proposed improvement. We eventually hit upon the idea of

incorporating a new variable: the power of the market in question, determined

by the sum of all the local references (i.e. all the references in the world

altered by their distance from the market in question). With this in hand, we returned to the

problem.

For gold, we have

I'll walk you

through this equation. The

product/global term gives us the crop size - how many units of a good are worth

1 reference. We then multiply our crop

size by the power of our market which tells us how many oz. of gold our economy

is worth (since 1 reference is equal in value to any other reference, we have

product/global*power value in our system as a whole). We divide this number by how many references

of gold we actually possess, local, and this gives us a ratio of the total

value of our system in gold by how many references for gold we actually

have. We convert this to copper coins

and are done.

Now to tackle

valuing goods. Working this morning, I

constructed the following expression:

The first term

calculates the value of the goods on hand in copper pieces. The second term scales that price by how

powerful our market is and how abundant the resource is - a resource with fewer

references will have a higher price than one with many, and a more powerful

market (drawing more things from more places) will command lower prices

overall.

Alexis' explanations

of his own steps are as good, if not better than mine. But the units of all of these expressions

work out, and now each good's price is influenced by the market's power and the

global and local reference values, increasing site-specific prices.

Of course, due to

the probabilistic process through which I generated my references, I may have

some correcting to do (I needed to add a bunch of iron references, for

example), and that may necessitate either adding more references or modifying

the production totals in order for the economy to work in the way that I need,

but I am much happier with these expressions.

Also, as a side note, VLOOKUP is a godsend in this work. No more hunting for appropriate references!

Thursday, September 15, 2016

Speaking of Sacred (Catholic) Music...

Reading for a class and I come across a section from Chris Page's book, The Christian West:

"Some time before 1123, Peter the abbot of Cava in Campania found that the local seigneur was sporadically emerging from his castrum of San Severino and harassing the workers on the rural estates of the monastery. He even drove them from one of the fields as they were in the midst of sowing. The lord's motives are unlikely to have been very complex; the archives of the abbey of Cava are extensive and they leave no doubt that the monastery owned a considerable amount of land. Lord Roger of San Severino had every reason to enlarge the scope of his tenantry by threatening its rural serfs as a prelude to appropriating its good arable land, and it would not have taken much for his group of armed and mounted men, the garrison of the castellum, to see off the abbey's peasants in the field. Instead of raising a militia or appealing to a diocesan, however, Abbot Peter decided to defend the furrows with plainsong. He went out to the field with the serfs and a few monks and 'instantly began to sing chant'. Lord Roger appeared with his men, but at the sound of the plainsong his mood was softened to the point where he became penitent, even lacrimose, and prostrated himself at the abbot's feet. 'Thus', says Peter's biographer, 'we know that psalmody softens the ferocity of evil spirits and puts them to flight.' (394)

Furthermore, we also get these gems:

"plainsong was a means of healing... it was also, as the miraculous appearance of saints during worship occasionally revealed, a form of conjuration." (394).

Some things to think about when considering how music might play a role in your worlds, especially your sacred music.

"Some time before 1123, Peter the abbot of Cava in Campania found that the local seigneur was sporadically emerging from his castrum of San Severino and harassing the workers on the rural estates of the monastery. He even drove them from one of the fields as they were in the midst of sowing. The lord's motives are unlikely to have been very complex; the archives of the abbey of Cava are extensive and they leave no doubt that the monastery owned a considerable amount of land. Lord Roger of San Severino had every reason to enlarge the scope of his tenantry by threatening its rural serfs as a prelude to appropriating its good arable land, and it would not have taken much for his group of armed and mounted men, the garrison of the castellum, to see off the abbey's peasants in the field. Instead of raising a militia or appealing to a diocesan, however, Abbot Peter decided to defend the furrows with plainsong. He went out to the field with the serfs and a few monks and 'instantly began to sing chant'. Lord Roger appeared with his men, but at the sound of the plainsong his mood was softened to the point where he became penitent, even lacrimose, and prostrated himself at the abbot's feet. 'Thus', says Peter's biographer, 'we know that psalmody softens the ferocity of evil spirits and puts them to flight.' (394)

Furthermore, we also get these gems:

"plainsong was a means of healing... it was also, as the miraculous appearance of saints during worship occasionally revealed, a form of conjuration." (394).

Some things to think about when considering how music might play a role in your worlds, especially your sacred music.

Friday, September 9, 2016

On the Humanist and Anti-Humanist Aesthetics of Ruin

So, I wrote the last post and then realized that I wasn't done thinking about ruins and how they

function in games. This is about aesthetics and draws a lot from the 19th century. You have been warned.

Ruin porn in art is

exploitative and harmful to the communities from which the images/artifacts are

taken. Ruins in fiction/games cannot be

harmful because no real persons are involved in the ruin - playing a game in a

ruin or ruined setting does not pull attention away from actual real people

living in actual Detroit who could really use some support or, even better,

some empathy.

Ruin settings are

about decay - things that were once larger than anything that have broken

and/or been corrupted into incoherency.

Now, I use ruins as well, as do many DMs and many games, but my ruins

look and feel very different from the ones Joseph Manola discusses in his

essay. Now, I'm sure one could chalk

that up to my adventures not being as 'good' as Red and Pleasant Land or Deep

Carbon Observatory, but that discussion is ultimately pointless. What I want to talk about are the aesthetics

that I perceive underlie some of those differences - what I'm calling humanist

and anti-humanist aesthetics of ruin.

I'll talk about

anti-humanist aesthetics first - they are primarily the subject of Manola's

essay. In an anti-humanist ruin, or an

anti-humanist conception of ruin, the ruined thing is a corruptive agent: it

taints those around it with ruin and entropy, meaning that anything encountered

nearby the ruin has been transmuted. The

idea is an inversion of the Arthurian connection between citizens and their

home - that a ruined environment perpetuates ruin in the people who dwell near

it. It is an explanation for all of the

madness and horror that often comes out of such a setting: not only is the ruin

itself inscrutable, but it is impossible to understand and/or empathize with

the inhabitants of the ruin, either.

That is not to say the party cannot ally with the inhabitants,

communicate in some way, but the ruin's denizens are fundamentally inhuman. Furthermore, the descent into ruin is

inevitable - the ruin cannot be repurposed, its inhabitants are doomed to their

vices and depravity. Order is ultimately

meaningless in the face of such a profound, sublime ruin. To borrow from Berlioz, darkness leads to

deeper darkness.

The humanist ruin

puts a different spin on the same setting.

It takes the same setting but makes two critical changes. The first is that many or most of the

inhabitants of the ruin are understandable; they follow Maslow's Hierarchy of

Needs or have some other set of goals to which the players might relate, even

if only slightly (or can be persuaded to temporarily cease their holy war

against the butter-side-ups to ensure that the demon of the deeps stays put,

since everyone dies if it comes out). If

we want to draw from romance fantasy, the relatable nature of the creatures

involved with such a ruin can be even more horrifying than those of the

anti-humanist aesthetic - it can become more personal to the players (not the

characters but the players) very quickly.

Often in this case, the only tools available to the players to have a

meaningful impact upon the space are their empathy and communication skills,

borrowing from the idea of romance fantasy.

The second change is that it is possible to impose order upon the ruin,

to find (or assign) a meaning to the ruin that gives it some understandable

function and a purpose to which it can now be used - it rewrites the ruined

nature of the setting and 'normalizes' it, aligning it with the rest of the

setting. To borrow from Beethoven,

darkness leads to light.

Now, these are

theories about gaming aesthetics, which means that rather than applying them to

adventures or settings or whatever, they have to be applied to actual games

being run (just as dramatic theory can only be fully applied to recorded

performances or live performances, not to scripts). However, I can pull a couple hypotheticals

from Zak S.'s Red and Pleasant Land

to show how both aesthetics can manifest within the setting.

The world of

R&PL is a ruin on every level - a war has been fought for an unknown amount

of time for reasons that make little logical sense. The topology of the region is non-Euclidean,

the denizens are range from apathetic to inimical to human life, and so

on. However, the Jabberwocky is a

symptom of the thwarted space-time continuum: by killing the Jabberwocky, the

time frame of the war is established and many of the spatial anomalies clear

up. Knowing, definitively, how long the

war has been waged gives players the ability to affect the war, presumably to

stop it, which allows order to come back into the region. A humanist DM lets the players know this

information and, if they desire this outcome, will enable them to do so (at

least eventually. It should be quite

challenging). The anti-humanist DM

doesn't particularly care about the Jabberwocky, and the only problem results

if the party wishes to impose order and the anti-humanist DM doesn't wish them

to do so (but that problem has less to do with the aesthetic position and more

to do with this particular DM being an asshole).

One of the more

interesting insights from Manola's post was his linking the LotFP/OSR ruin

aesthetic with the Sublime, an aesthetic phenomena associated with the Long

19th century, and it bears a strong resemblance to the kinds of settings run

under the anti-humanist aesthetic of ruin.

Of course, one of

the other strong themes from the Long 19th century was that of the triumphant

hero who struggles against dark forces and ultimately triumphs, which is

certainly one of the potential outcomes from this humanist aesthetic of ruin.

Ruin porn

One of the blogs that I read, and was instrumental in working towards a minimal but highly functional design framework, is Roles, Rules, and Rolls, by Roger G-S. He just linked to Joseph Manola's post on the LotFP circle, as well as a number of other, linked writers, game designers, and thinkers, and one of the common aesthetics they share - the idea of ruin. The essay is absolutely worth reading and connects to a number of much older artistic models for this fascination with ruins (Zdzislaw Beksinski and Hubert Robert, for example).

However, there is also a modern fascination with ruins beyond 18th and 20th c. artists, namely that of ruin porn. I first came into contact with the concept at a presentation on the birth of techno, which happened toward the end of the 20th c. in Detroit, which opened discussing this art installation. In photography and sculpture, ruin porn can be highly exploitative - because such works are intimately linked with a geographic area, the images of ruin come to represent the whole area, regardless of whatever action is being taken to remedy the lives and communities actually damaged by the ruin.

I think that it is highly interesting that in this post-Soviet era, where the myth of American Exceptionalism is no longer taken as literal truth by many, where small groups of individuals can wield tremendous power in global geopolitics, and democratic governments stagnate and fail to govern while the electorate that could drive positive change simply sits and simmers we find not only ruin porn, but also people choosing to create and inhabit fantasy worlds filled with dead and decaying things, through whose remains they pick.

However, there is also a modern fascination with ruins beyond 18th and 20th c. artists, namely that of ruin porn. I first came into contact with the concept at a presentation on the birth of techno, which happened toward the end of the 20th c. in Detroit, which opened discussing this art installation. In photography and sculpture, ruin porn can be highly exploitative - because such works are intimately linked with a geographic area, the images of ruin come to represent the whole area, regardless of whatever action is being taken to remedy the lives and communities actually damaged by the ruin.

I think that it is highly interesting that in this post-Soviet era, where the myth of American Exceptionalism is no longer taken as literal truth by many, where small groups of individuals can wield tremendous power in global geopolitics, and democratic governments stagnate and fail to govern while the electorate that could drive positive change simply sits and simmers we find not only ruin porn, but also people choosing to create and inhabit fantasy worlds filled with dead and decaying things, through whose remains they pick.

Refining the Trade System

I'm hard at work

with classes as well as implementing Alexis' trade system right now and I

wanted to document some of the ways I've needed to change the process in order

to create the outcome I want.

The trade system

depends upon references of goods bound to specific commercial locations

(markets) where goods of that type are either produced or gathered from nearby,

noncommercial areas (outlying farms, smaller towns, shipped downriver, etc.). Following Alexis' suggestions, I plotted out

regions of influence for each city, ranging in size from 4ish hexes for the

smaller cities to 15 or 20 for the larger ones.

I initially used Welshpiper's medieval settlements calculator to

determine how many cities I ought to have in regions of a given size and

population density, which lead to more cities than I had reasonable room to

place. I did what I could - and I think

the map has benefited from the density of locations in both the Southern

Kingdoms and Confederacy (I scaled back the city counts intentionally for Arein

because of its relatively young age (60 years)). Obviously, the more closely packed the cities

are, the fewer hexes each controls within a given area.

Each hex controlled

by a market might produce resources, based upon its hydrology, elevation, and

level of civilization. While I haven't

implemented Alexis' idea of infrastructure numbers yet, it is a future project. As a rule of thumb, I decided that any hex

more than two hexes away from the closest city was undeveloped and thus (for my

two heavily-treed areas) still jungle/forest.

Hexes only 40 miles (2 hexes) from the closest city were also

undeveloped, but if there was another city within 2 hexes from the are in

question, the hex is settled instead.

It may be helpful to take a gander at the map I uploaded recently.

One of the early

difficulties I encountered with the random determination is that Alexis'

regions are based upon the kinds of terrain found in, say, Hexographer, rather

than rooted in any kind of elevation or topological scheme, which is how I

built my world. While I absolutely

understand the desire to be accessible, I had a little bit of work to do to

adjust it. My first approach was to

classify any hex adjacent to another hex with an elevation difference of 400 or

more counted as a hill (which graduated to mountain as soon as the hex's height

breached 2000' above sea level). This

gave me no hills because the elevation change was smoother than I had

anticipated. My second approach banded

hexes by color: hexes over 500' but under 2000' were hills, hexes over 2000'

were mountains, and hexes between sea level and 500' were flat, either plains

or scrublands (hexes between -50' and 0', found only at the coast, became

marshes). Alexis' plains designation

really applies to land used for large-scale farming, whereas scrubland does

not. Thus, hexes 1 hex or closer to a

city are plains, while those that I've ruled undeveloped are either scrub or

forest/jungle. Now, deciding between the

two choices was tricky. They are

entirely different vegetation systems, and it was important that I get the

resources from both. I still don't have

a satisfactory answer, but the answer I used had to do with distance from the

forest's center, something for which I had a rough location.

The biggest change I

needed to make was further differentiating the very generic labels of building

stone, cereals, fruits (which replace grapes, since I'm in a tropical

environment), gems, and vegetables.

My world's central

distinguishing characteristic is the differences in both outlook and material

culture between each of my societies.

Therefore, I need to be able to distinguish between the kinds of

resources available to each people, as well as what specific foods is grown to

determine diet and food culture. I have

a sedimentary ridge that separates the Confederacy and Southern Kingdoms, and

so I used that to distinguish between the kinds of stone found: south of the

ridge is sandstone, compressed sediment from the sea, while north of the ridge

is limestone because of the karst topology (a choice I made to provide

sinkholes to the area). Across the Sea

of Shadows to the south, I have granite mountains.

However, karst

topology includes important things like dolomite and gypsum, which I wanted to

produce as well, and this led me to the solution I employed for my other

reference specifications. I assigned

probabilities to each type and rolled a die: 1 dolomite, 2 gypsum, 3-4

limestone. The important thing is that I

get different numbers for each resource, scattered throughout the regions.

I then specified

different cereal categories, millet, rice, and wheat, fruit categories,

bananas, coconuts, mangos, and pineapples, gem categories, ornamental, fancy,

semiprecious, lesser precious, and greater precious, and vegetables, cassava,

cotton, edibles (tubers and the like), jute, palm oil, and soybeans. I determined these the same way, giving each

a probability and then rolling for each individual reference - I tried applying

a strict percentage on the overall reference to give me numbers, but the

results were too clean.

The last way I've

changed the references is adding a new one: warcraft, which governs the making

of arms and armor for a given culture.

The Tarluskani use a khanda while the Southerners use a longsword. While they are similar in many ways, the

techniques to use it are different, as are the concerns and problems when

forging it. This also lets me price

weapons and armor from different cultures like the exotic or commonplace items

they are, even though the skills involved are the same. I get my Warcraft value for each market from

the sum of the leathercraft, metalcraft, and woodcraft references, since they

are highly related industries.

My last change to

the overall system was in using the reference numbers to populate information

about the cities themselves. It follows

that cities with higher references are more economically powerful than those with

a lower count - they have more resources

and can bring more to bear to any economic dispute. So, since the urban population of the late

Middle Ages was something like 25% of the total population, I have calculated

the total population for each area based on population density (usually between

10-20 people per square mile), multiplied it by .25 and the multiplied it by

the ratio of the market's reference total compared with the region's reference

total to get the final population.

For example,

Reyjadin is the capital city of the Southern Kingdoms. Being a capital city, I've doubled its

population because of that added importance.

The total population for the Southern Kingdoms is approximately 683,000

people. Reyjadin controls 6 references

while the Southern Kingdoms as a whole controls 291 references. So, Reyjadin's popullation is

683,000*.25*2*(6/291)=7,041 people.

Population then defines a city's physical size (population/38850 square

miles) and the strength of its guard (population/150 employed guards). While obviously these latter two measures are

adjustable, it gives me a systematic way to approach any city.

While there's a lot to refine about this process (like using the total local references rather than references controlled by the market), it's definitely progress.

Also, a helpful resource to intrepid worldbuilders.

Also, a helpful resource to intrepid worldbuilders.

Tuesday, September 6, 2016

Trade Tables

Week two of graduate school, and I already foresee my free time dwindling from what I had this summer. However, I've still been working on my world - I finished calculating the distances between all 69 cities as well as calculating the references governed by each city. With that step finished, I am now adapting Alexis' trade tables for my own purposes. Because I am one of his Patreon backers, I have access to his most recent full table, which I am unabashedly plundering.

The process, which I have but barely begun, makes me aware of the massive size of the trade tables as well as the work that has gone into them. I will be pleased to get my much reduced version off of the ground for my players to enjoy.

The process, which I have but barely begun, makes me aware of the massive size of the trade tables as well as the work that has gone into them. I will be pleased to get my much reduced version off of the ground for my players to enjoy.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)