I'm also instituting a rather large change to how I run combats based on Alexis' use of action points. It is an elegant solution to a complicated problem, and I've wanted to adapt it to my game practically since I first encountered it. Because combat is the one area in the game where characters are most directly threatened, the combat rules need to be very clear and very fair. These rules do that, allowing me to account for most of the actions my players might undertake yet remaining flexible and easy to implement.

First, let's talk about clashing. The basic idea is that during battle, combatants cluster into larger engagements. Rather than trying to model each line of attack and defense, I want a single roll to determine which "side" in the engagement triumphs in a given round.

The best fighter on each team determines the starting difficulty, and the number of fighters on their team then adds a bonus. NPCs have a static difficulty, and the player controlling the best fighter on the players' team rolls. On a success, the players deal damage based upon the rolling player's character's weapon and the difference between the result and the difficulty. Damage is distributed among the defending creatures according to the most-skilled defender. On a failure, the players take damage, and the rolling player determines how the damage is split among the different characters on their team.

Consider the following situation:

One player character (right) is faced by two brigands (left). I use 1-yard hexes, so while each fighter is physically situated in a single hex, their weapon extends into all adjacent hexes. Since no one's weapons touch, no one is fighting, and there is no clash.

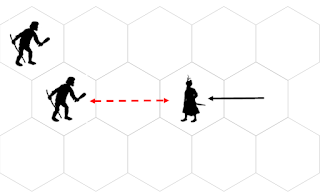

The player moves into combat, and they are now clashing. With one brigand versus one character, the player controlling that character rolls a Combatant test against the skill rank of the brigand, with no modifiers to either party. If both are Apprentice rank, the player rolls 1d4+1d6+attribute, hoping to roll equal to or above a 9.

When the second brigand engages the character, things turn a little dire. Because there is one more brigand than character, the brigands get a +3 bonus; the player still rolls 1d4+1d6+attribute but now must equal or exceed a 12. If there was an additional brigand in the clash, the player would then need to roll equal to or in excess of a 15.

When the character's friend appears and rushes into combat, the sides are now equal. Even though the second character does not threaten the first, they are all still part of the same clash because we can connect all of the fighters together. Because both sides have an equal number of fighters, no side gets a bonus. If the second character is a Professional-rank fighter, they would roll for the clash, comparing their 2d4+1d6+attribute against the brigands' 9. If the second character is Apprentice-rank, the first character would roll because they are targeted by more enemies. If the second character was a Combatant Novice, the first character would roll because they are the better fighter.

This clash is still 2v2 because we can connect all of the fighters.

In this example, however, we cannot connect all of the fighters. Each character is a member of a different clash and will roll separately. (We can think of clashes as graphs set upon a set of vertices. Each combatant is a vertex, and we connect two vertices if their weapons overlap and they are on opposing teams. Each resulting graph is a clash)

For Action Points, I rely on Alexis' wiki article on the topic. I need to make only a few changes.

Characters have a number of AP equal to their speed (which is racially-determined and affected by both encumbrance and injuries)

Characters in a clash lose 2AP (instead of using 2AP to attack). This loss happens as soon as they enter a clash (potentially ending their turn), and at the beginning of any turn in which a character is within a clash.

Disengaging from an opponent requires 1AP per opponent disengaged in addition to whatever AP are spent on the movement itself.